Although workers in 94% of American jobs pay into Social Security, a small segment of the population — most of whom work for state and local governments — do not. Since workers in these jobs do not pay Social Security payroll taxes, those who contribute to Social Security for a portion of their career end up getting a greater return on the taxes they do contribute to the program than other Americans with similar lifetime earnings. To address this issue, Congress passed the Government Pension Offset (GPO) and Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) in the late 1970s and early 1980s as an attempt to provide comparable benefits to these workers.

Now, a bipartisan coalition in the House is pushing to repeal these provisions. While it is true the WEP and GPO are imperfect solutions that can unfairly punish some low-income public workers, Congress would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater if they repealed the provisions altogether. Instead of overcorrecting and providing excessively generous benefits to a small cohort of Americans, Congress should consider a proportional benefits system that reduces benefits based on the individual’s contributions to the Social Security program. Not only is this reform the most equitable solution to an important problem, but it remains more in line with the intention of the WEP and GPO.

Why are the WEP and GPO necessary?

Social Security benefits are designed to be progressive, meaning that low-income individuals will receive a greater benefit for each dollar they paid into the program through payroll taxes than higher-income individuals. To determine one’s benefit, the average of an individual’s highest 35 years of covered earnings is used to calculate their average indexed monthly earnings (AIME). Individuals receive a benefit equal to 90% of their AIME up to the threshold of $1,115. This percentage decreases as lifetime earnings increase, with beneficiaries receiving 32% of each dollar of their AIME between $1,115 and $6,721, and 15% of each dollar of their AIME that exceeds $6,721 up to a maximum of $13,584.86.

Importantly, the AIME formula only incorporates earnings on which employees and their employers pay payroll taxes. Many state and local government jobs are considered uncovered since their employees do not pay Social Security payroll taxes. Instead, these employees contribute to pension plans. Since these employees don’t contribute to Social Security through taxes, their annual covered earnings are zero for each year that they work at an uncovered job. As a result, a high-income worker with many years of uncovered employment would appear to have the same AIME as a worker with a lifetime of low-income employment.

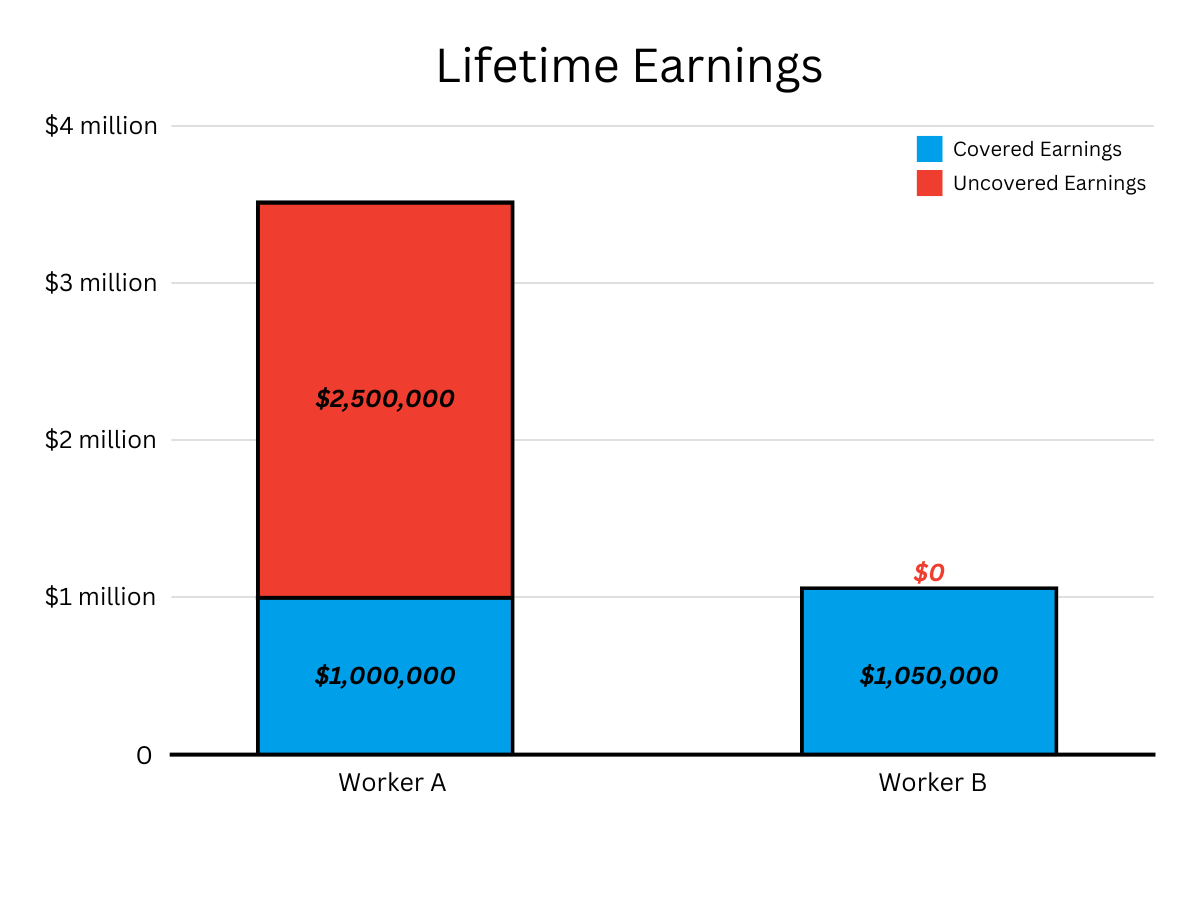

Here’s an example: Worker A makes a steady, inflation-adjusted salary of $100,000 during his 35 years of employment, 10 of which were spent in the private sector. Worker B is a low-income worker in the private sector who makes $30,000 annually. The following graph shows their total lifetime earnings, split between covered and uncovered earnings.

Despite Worker A making nearly four times as much as Worker B, most of Worker A’s earnings are uncovered, meaning that the Social Security benefit formula treats them both as low-income earners and would provide them roughly the same level of benefits.

This formula also results in Worker A getting better treatment than workers with comparable earnings in the private sector. Worker A’s Social Security benefits would replace roughly 59% of his AIME, a relatively high replacement rate meant to assist low-income workers. In comparison, a worker who had the same average salary as Worker A in the private sector would only have a replacement rate of 36%. Without adjustments to the benefits formulas, the high-income public sector workers would be receiving a significantly higher return for each dollar of income on which they paid payroll taxes, representing an unjustified windfall.

The WEP and GPO remain imperfect solutions that disproportionately harm low-income government workers.

The WEP reduces the replacement rate that qualifying individuals receive for their first $1,115 of covered earnings. Rather than receiving 90% of the $1,115 in benefits, the replacement rate for government workers is as low as 40% depending on how many years of covered employment they have. The GPO applies complementary adjustments to spousal and survivor benefits.

This formula leads to proportionally larger benefit reductions for government workers with low AIMEs, leading critics to argue that it is regressive. Since the provisions only affect the earnings made up to the $1,115 of covered earnings, qualifying individuals who have a lower AIME lose a greater share of their total potential Social Security benefit because of these provisions than those who have an AIME over $1,115. For instance, a high-income worker who consistently makes an annual salary of $120,000 over 35 years and spent 10 of those years in the private sector would have their benefits reduced by 36%. On the other hand, a lower-income worker who spent 25 years paying payroll taxes and makes $45,000 a year would have their benefits reduced by 42% under the current law, despite paying into the Social Security program for a longer period.

Additionally, the current wage reduction is not an accurate method of adjusting benefits fairly. WEP and GPO were designed to adjust Social Security benefits so that they are relatively proportional to the length of time they paid into the program. A worker who worked in the private sector for 40% of their career should receive about 40% of the benefits that a worker with similar earnings would receive if they worked their full career in the private sector. However, when these provisions were passed in the 1970s and 80s, the SSA lacked adequate data to make precise adjustments. Instead, the provisions relied upon a roughly approximated formula that has led to benefits being over- or under-adjusted, depending on an individual’s distribution of covered and noncovered earnings.

Repealing the WEP/GPO would create new equity problems and threaten the fiscal security of the trust fund.

In response to criticism about the provisions, Members of Congress have proposed repealing both provisions in the Social Security Fairness Act, which has been garnered bipartisan support in both the House and Senate. However, despite the issues with the current formula, a complete repeal of the WEP and GPO would be costly and unfair to other Americans who paid into Social Security throughout their career.

Eliminating these two provisions would increase benefits for the 2 million individuals that have not sufficiently paid into Social Security through payroll taxes. Unlike individuals who have spent their whole careers in covered jobs contributing to the Social Security program, these individuals spent a portion of their career in jobs not subject to Social Security payroll taxes. As previously noted, they pay into pension plans during their time at uncovered jobs and upon retirement, receive pension benefits on top of Social Security benefits.

If these individuals began receiving non-adjusted Social Security benefits on top of the pension benefits, their total retirement benefits would replace a larger percentage of their lifetime earnings than the benefits of those who worked in covered jobs for their entire career. This outcome would run counter to the intention of the Social Security program, which is intended to provide low-income individuals the most support by replacing a higher percentage of their income.

Additionally, repealing the WEP and GPO would worsen the already financially insecure Social Security trust funds, which are slated to be exhausted after 2032. By increasing benefits for 2 million retirees, a complete repeal is estimated to cost $182.8 billion in ten years, pushing up the date of OASI and DI trust fund insolvency — and the 23% across-the-board benefit cut it would trigger for all beneficiaries — by six months to a year.

Proportional Social Security benefits would mitigate current issues with the WEP and GPO without providing uncovered employees an unjustified windfall.

To make the Social Security system more equitable, Congress should adjust the benefit reduction formula for public employees to more accurately account for their covered earnings. Now that the Social Security Administration collects data on non-covered earnings, the GPO and WEP should be reformed to keep in line with the initial intention behind the provisions. Congress should amend the benefit reduction formula to make reductions proportional to the ratio of an individual’s covered earnings to their total earnings, a solution previously proposed by Reps. Brady and Neal in the Equal Treatment of Public Servants Act of 2015. This proposal would apply the current benefits formula to the “Super AIME,” which is calculated with both covered and uncovered earnings. These benefits would, then, be adjusted by multiplying it by the percentage of total earnings that were covered.

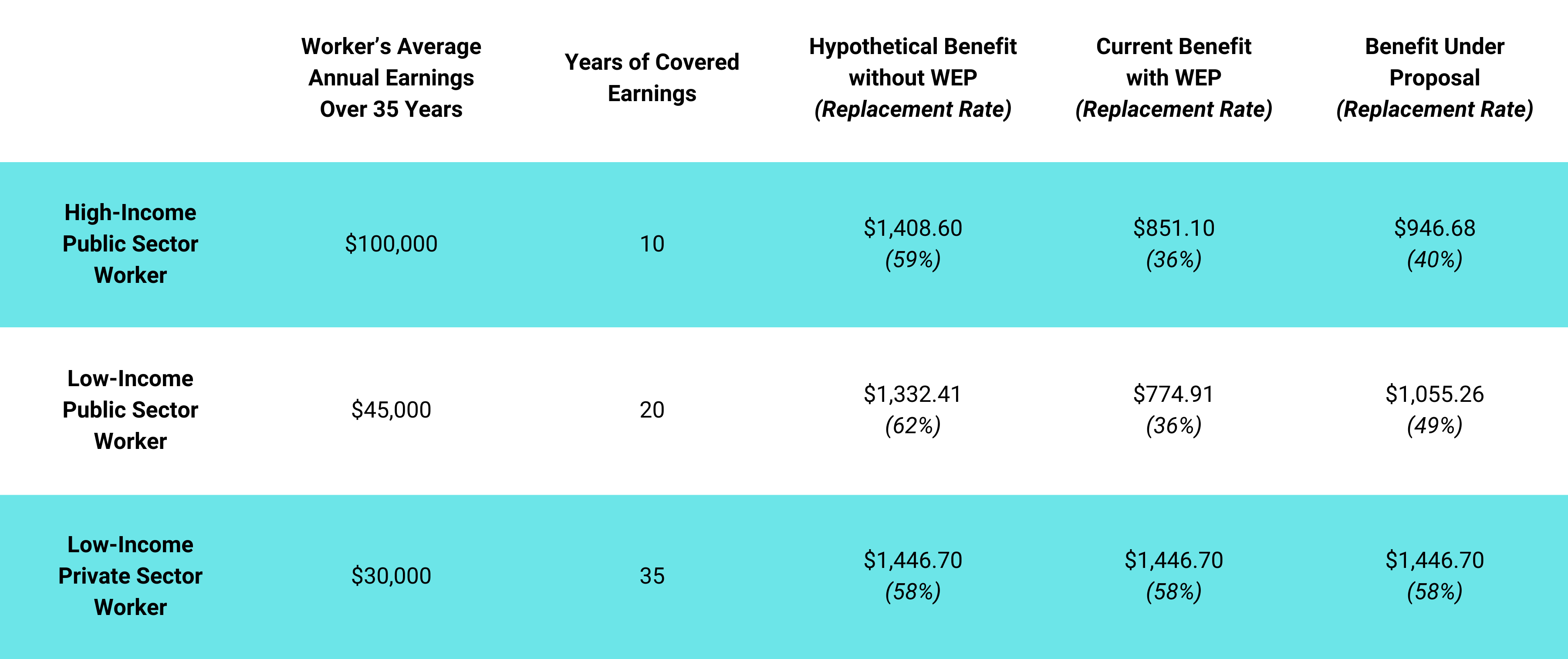

Here are three hypothetical workers to demonstrate how the new proposal would work in practice:

The above table shows the hypothetical benefits that these three individuals would receive if a) the WEP and GPO were repealed, b) under current law, and c) under a proportional benefits formula.

Under the current law, the low-income public sector worker sees a larger cut in their Social Security benefits than the high-income public sector worker, reflecting the issue that the current formula has with accurately adjusting benefits. However, if the WEP and GPO are repealed, the high-income public sector worker’s benefits would be roughly the same amount as low-income workers. As discussed above, this means that the high-income public sector worker would be receiving an unjustifiably high replacement rate that similar workers in the private sector do not. In contrast, the proportional formula would adjust their benefits based on their length of covered employment. In this example, the low-income public sector worker, who spent double the time in the private sector paying payroll taxes, will receive more benefits to account for the different lengths spent in covered employment.

Private sector workers would not be affected by this reform. Their benefits, which have not been affected by the existing WEP/GPO provisions, would remain at the same level under the proportional system.

Ultimately, Social Security benefits should be updated to better reflect the original intentions of the WEP and GPO adjustments, as well as maintain its progressivity for public sector retirees. Reforming the program to make Social Security benefits proportional to the length of covered employment would allow all retirees, both covered and noncovered, to receive their fair share of benefits.