As we move into 2023, the digital sector still faces the key regulatory issues that dominated the previous year: Competition, privacy, and content moderation. But as the legislative, executive, and judicial branches tackle these critical questions, it is important to look back and assess the performance of the digital sector on the key economic metrics of job growth and inflation.

For clarity we split the digital sector into three subsectors:

- E-commerce/retail (“movement of goods”)

- Internet/content/broadband (“movement of data”)

- Computer/communication manufacturing (“hardware”)

E-commerce/retail: To compete with e-commerce leaders such as Amazon, retailers with a large physical presence such as Walmart and Target have been scaling up their investment in online sales and fulfillment. At the same time, smaller retailers increasingly use online ordering, so the boundary between “brick-and-mortar” and e-commerce has become increasingly porous. Moreover, privacy and content moderation issues such as accountability for user reviews impact all retailers. In addition to retail, this subsector also includes local delivery (NAICS 492) and fulfillment (NAICS 493).

Internet/content/broadband: With the advent of social networks and streaming, the line between content creation and content distribution has become blurry. Considerations of privacy and content moderation are high on the policy checklist. This subsector includes content creation and distribution (video, audio, print); broadband and broadcasting; wireless; software; internet publishing and search; and computer systems design.

Hardware: Especially with the funding from the CHIPS Act and the focus on export controls, this subsector is facing a different set of policy issues. We include computer and electronic equipment manufacturing, and related wholesaling.

Job Growth

(Note:These figures have been updated to account for the 2/3/23 revisions to the job data)

As of December 2022, the United States currently enjoys a 3.5% unemployment rate, the same as pre-pandemic February 2020. To a large extent, this strong labor market has been driven by job growth in the digital sector. In total the digital sector added 1.4 million net new jobs from 2019 to 2022, accounting for 67% of net private sector job gains over the same period. Table 1 breaks down the pandemic job growth by digital subsector.

We see that the e-commerce/retail subsector accounted for net job growth of 926,000 jobs from 2019 to 2022, or 44% of private sector job growth, as consumers embraced online shopping during the pandemic, and retailers and third-party logistics companies built and staffed fulfillment centers.

The internet/content/broadband subsector created 472,000 jobs, accounting for 22% of private sector job growth. Altogether, the digital sector accounted for 67% of private sector job growth from 2019 to 2022.

The importance of the digital sector for job growth is emphasized when we look at production and nonsupervisory workers, who generally are less educated and lower-paid (Table 2). The digital sector has created 1.1 million net new production and nonsupervisory jobs from 2019 to 2022, while the rest of the private sector has lost almost 500,000 production and nonsupervisory jobs.

In particular, the e-commerce/retail subsector has added 812,000 production and nonsupervisory jobs during the three pandemic years. That’s likely to reflect the growth of e-commerce fulfillment and delivery workers. This gain was essential to the recovery because the rest of the private sector has still not regained its pre-pandemic level of production and nonsupervisory employment.

From the perspective of policy, the current regulatory structure turned out to encourage strong job growth in a difficult economic environment. That’s not to say the current regulations cannot be improved, but we should be wary of making major changes without understanding the consequences for jobs.

| Table 1. Digital Sector Drives Job Growth During Pandemic |

|

2019-2022 |

|

Increase in jobs, thousands |

Share of private sector growth |

| Private sector |

2,133 |

|

| E-commerce/retail* |

926 |

44% |

| Internet/content/broadband** |

473 |

22% |

| Hardware*** |

22 |

1% |

| Data: BLS, PPI calculations |

|

|

| Table 2. …Especially for Production and Nonsupervisory Jobs |

|

2019- 2022 |

|

Increase in production and nonsupervisory jobs, thousands |

Share of private sector growth |

| Private sector |

665 |

|

| E-commerce/retail* |

812 |

122% |

| Internet/content/broadband** |

306 |

46% |

| Hardware*** |

24 |

4% |

| Data: BLS, PPI calculations |

|

|

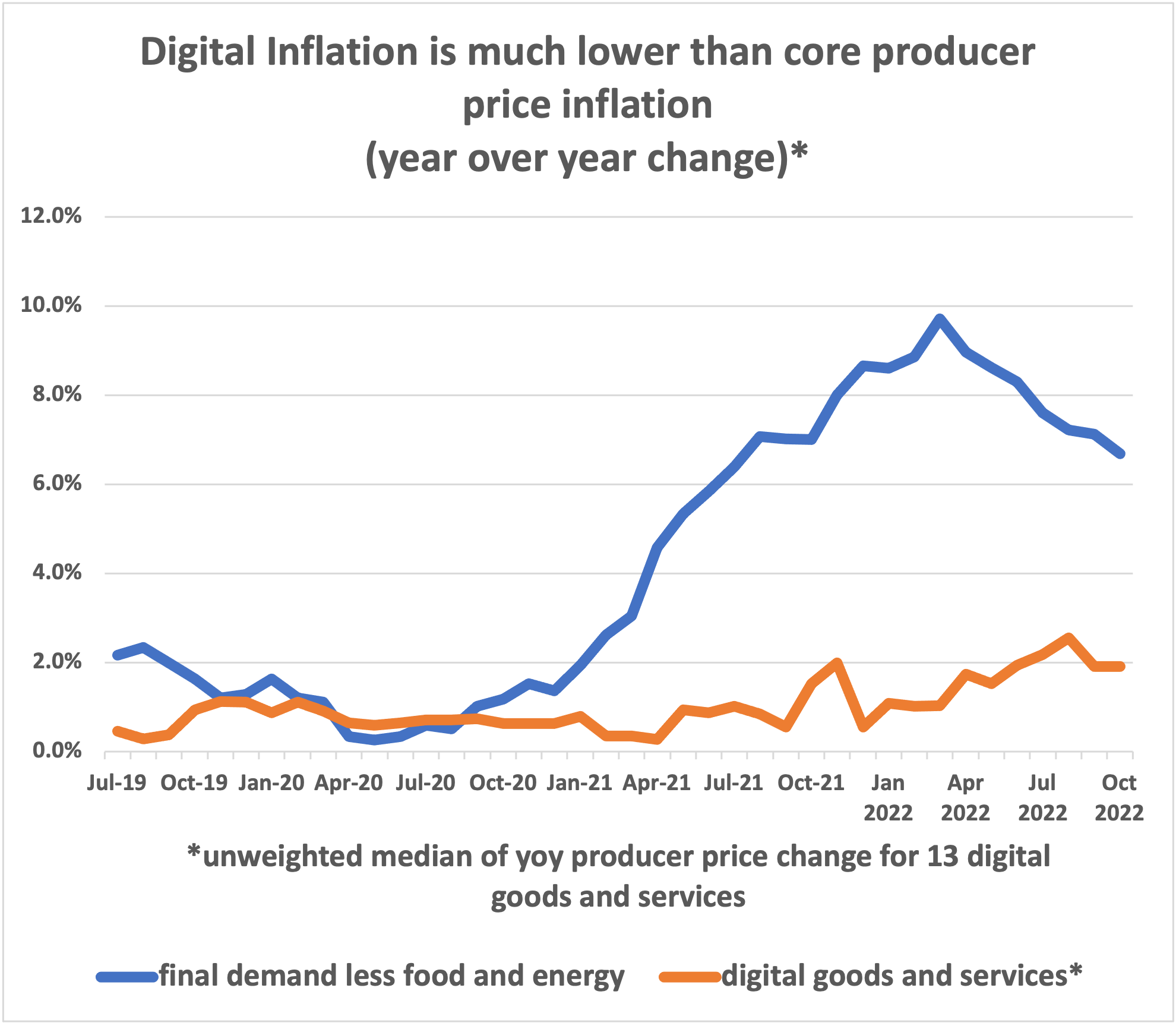

Inflation

Before the pandemic, the digital sector had significantly lower inflation than the economy as a whole, whether measured by producer prices or consumer prices. During the pandemic period, overall consumer price inflation accelerated by approximately 3 percentage points, from roughly 1.5% annually in the pre-pandemic period (2012-2019) to roughly 4.5% annually during the pandemic years (2019-2022).

However, the acceleration of inflation was much smaller in the digital subsectors. For example, inflation in the internet/content/broadband subsector only accelerated by 0.3 percentage points when measured by producer prices, and 1.7 percentage points when measured by consumer prices.

Please note that the BLS does not publish a separate measure of e-commerce inflation for consumer goods and services, which is why that line is missing from Table 4. However, in a 2022 paper written for PPI’s Innovation Frontier Project, Marshall Reinsdorf wrote that “the pandemic greatly accelerated adoption of digital innovations such as e-commerce, so it’s reasonable to suspect that the price statistics are undercounting the impact of low digital inflation.”

From the perspective of policy, it’s reasonable to say that the current regulatory structure allowed digital companies to behave in a way that muted the pressure to increase prices. Especially given the inflationary bias in today’s economy, the government should be wary of making changes that impose large new costs on digital companies.

| Table 3. Digital Producer Price Inflation Stays Low |

|

|

Average annual price increase |

|

2012-2019 |

2019-2022 |

Increase in inflation rate, percentage points |

| Final demand less food and energy |

1.7% |

4.7% |

3.0% |

| Electronic and mail order shopping services* |

1.5% |

1.8% |

0.3% |

| Internet/content/broadband** |

0.7% |

1.6% |

0.9% |

| Hardware*** |

-1.0% |

1.1% |

2.1% |

Based on median inflation for subsectors with multiple products or industries.

Data: BLS, PPI calculations

| Table 4. Digital Consumer Price Inflation Stays Low |

|

Average percentage price increase |

|

2012-2019 |

2019-2022 |

Increase in inflation rate, percentage points |

| Consumer prices |

1.5% |

4.6% |

3.1% |

| Internet/content/broadband** |

-0.4% |

1.3% |

1.7% |

| Hardware*** |

-7.6% |

-5.6% |

1.9% |

Based on median inflation for subsectors with multiple products or industries.

Data: BLS, PPI calculations

Appendix: Categories

In this section we define the three digital subsectors, and which statistical series we use to calculate jobs, producer price inflation, and consumer price inflation for each of them. Please note that for subsector inflation measures, we aggregate multiple price series using median inflation rather than weighted means.

*E-commerce/retail

In previous work, we distinguished between ecommerce and brick-and-mortar retail. That distinction is no longer appropriate, because retailers with large physical presence such as have also been building out their online ordering and fulfillment operations. Moreover, the latest NAICS codes do not break out electronic shopping as a separate industry anymore.

Employment data

- Retail sector (including online ordering and fulfillment operations for single companies)

- Couriers and messengers (including local delivery)

- Warehousing and storage (including fulfillment centers)

Producer price inflation data

- Electronic and mail order shopping services

** Internet/content/broadband

In earlier work, we used a narrower definition of tech. As barriers have become blurred between content and distribution, and various modes of distribution, it has become appropriate to broaden the definitions.

Employment data

- Motion picture and sound recording industries

- Publishing industries, including software

- Broadcasting and content providers, including social networks and streaming services

- Telecommunications

- Computing infrastructure providers, data processing, and web hosting, including cloud computing

- Web search portals, libraries, archives, and other information services.

- Computer systems design and related services

Producer price inflation data

- Bundled access services

- Cable and other subscription programming

- Data processing and related services

- Internet access services

- Internet publishing and web search portals (including advertising)

- Software publishers

- Video programming distribution

- Wireless telecommunications carriers

- Information technology (IT) technical support and consulting services (partial)

Consumer price inflation data

- Wireless telecom services

- Residential telecom services

- Internet services and electronic information providers

- Cable and satellite television service

- Video discs and other media

- Recorded music and music subscriptions

***Hardware

In previous work, we did not split out hardware. But the recent CHIPS legislation, and the focus on rebuilding the U.S. domestic semiconductor industry, means that it is appropriate to break out hardware separately. We note that the employment data includes relevant wholesalers, who may be “factoryless” firms designing and marketing digital products, but not actually manufacturing them.

Employment data

- Computer and electronic product manufacturing

- Computer and computer peripheral equipment and software merchant wholesalers

Producer price inflation data

- Communications equipment manufacturing

- Computer & peripheral equipment manufacturing

- Semiconductor and other electronic component manufacturing

Consumer price inflation data

- Computers and peripherals

- Computer software

- Telephone hardware, calculators, and other consumer information items

- Televisions

Left to right: Jordan Shapiro, Director of the Innovation Frontier Project, Progressive Policy Institute; Maryam Cope, Head of Government Affairs, ASML; Adrienne Elrod, Director of External Affairs for the CHIPS Program Office at the Department of Commerce.

Left to right: Jordan Shapiro, Director of the Innovation Frontier Project, Progressive Policy Institute; Maryam Cope, Head of Government Affairs, ASML; Adrienne Elrod, Director of External Affairs for the CHIPS Program Office at the Department of Commerce.