Entrepreneurship is the engine of long-term economic growth and dynamism. For the United States in particular, foreign-born entrepreneurs have made up an extraordinary share of our most successful companies and technological achievements. To encourage the vitally important flow of immigrant entrepreneurs, and to accommodate the growing need for an entrepreneur-specific pathway into the country, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) adopted the International Entrepreneur Rule (IER) in early 2017.

The rule was quickly put on hold by the incoming Trump Administration, but was never removed from the Code of Federal Regulations. With support from the new Biden Administration, the IER could quickly become an essential pathway to attract and retain foreign-born entrepreneurs who seek to build their businesses within the United States.

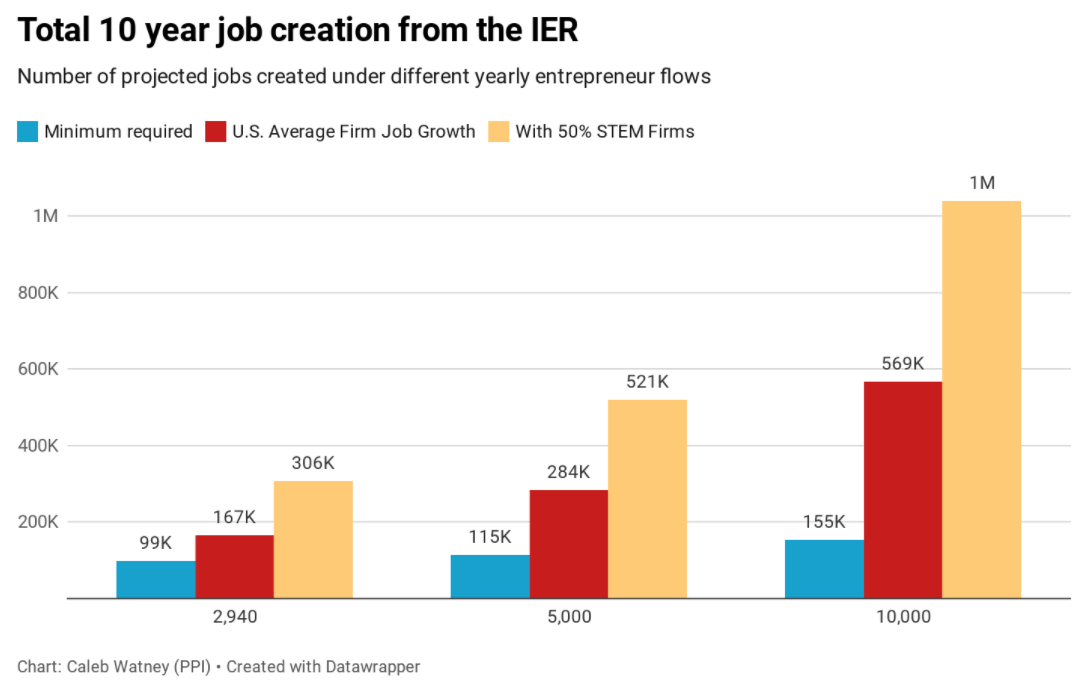

Using the DHS estimate that 2,940 entrepreneurs per year would come to the country through the IER, after adjusting for expected business failure rates, we project these entrepreneurs would produce approximately 100,000 jobs over ten years if they produce only the minimum number required for parole extension. If they mirror the average job growth of firms their age, we project more than 160,000 jobs over ten years. If 50 percent of them are high-growth STEM firms, we project more than 300,000 jobs over ten years.

If the number of yearly entrepreneurs is larger than DHS projected, job growth could be considerably higher:

This paper proposes the following recommendations for the new administration, both immediate and longer-term:

More than half of America’s billion-dollar startups were founded by immigrants, and 80 percent have immigrants in a core product design or management role. Though immigrants make up only 18 percent of our workforce, they have won 39 percent of our Nobel Prizes in science, comprise 31 percent of our Ph.D. population, and produce 28 percent of our high-quality patents. To be clear, this is not because immigrants are inherently smarter than the average native-born worker, but instead because of strong selection effects wherein many of the talented and entrepreneurial people from many countries are the individuals most likely to emigrate in search of new opportunities.

Importantly, global competition for this population of international entrepreneurs is heating up rapidly. Countries like Canada, Australia, and the U.K. have adopted versions of a startup visa to create a dedicated pathway for international entrepreneurs, while other countries like China have elaborate talent recruitment programs to try and bring back talented students and workers who are living internationally.

In contrast to this global trend, the United States does not have a statutory startup visa category, and trying to use traditional pathways such as the H-1B visa can be very difficult for an entrepreneur, if not impossible. Other pathways for highly skilled immigrants, including the O-1, EB-1, and EB-2 visas, rely on a strong record of prior accomplishments and are not a good fit for entrepreneurs whose potential accomplishments lie in the future. Entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs or Bill Gates had little track record of success before founding Apple and Microsoft; if they had been born in another country, it is unlikely that traditional employment-based U.S. immigration pathways would have let them start their respective firms here. This inability to recognize prospective success is one of the core deficiencies in our immigration system that the IER was designed to address.

Unfortunately, much damage has been done to the United States’ reputation as the prime destination for the world’s inventors and technical practitioners over the last four years. It is vitally important that under the new administration, we begin attracting this valuable global talent again and opening pathways for their legal residence. The IER has the advantage of already existing⸺quite literally⸺in the federal rulebook, and so it can be revived immediately. For policymakers looking to quickly re-establish the United States as the top stop for international entrepreneurs, strengthening the IER should be an appealing first step.

The Biden administration has made it clear that immigration makes the U.S. a stronger, more dynamic country. Nowhere is this more obvious than with international entrepreneurs who very directly grow the pie of economic opportunity for native-born Americans. The political moment is ripe for action on immigration with public support for increasing immigration at record highs ⸺ high-skill immigration is especially popular receiving support from 78 percent of the U.S. population.

Importantly, this proposal is complementary with the wide array of immigration proposals already being pursued by this administration. The IER operates through parole authority that does not impact existing visa caps for other programs, and not needing legislation or immediate regulatory action to operate means the IER is low-hanging fruit from an administrative perspective.

The IER was finalized at the end of the Obama Administration as a way for the federal government to attract entrepreneurs to launch innovative startups in the United States. It is a federal regulation that was developed by DHS, rooted in the DHS Secretary’s statutory authority to grant parole on a case-by-case basis for “urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.” (In the context of immigration law, “parole” simply means temporary permission to be in the United States; it has nothing to do with “parole” in the context of criminal law.)

The Secretary’s discretionary parole power has historically been used for those with serious medical conditions who must seek treatment in the United States, individuals who are required to testify in court, individuals cooperating with law enforcement agencies, and volunteers who are assisting U.S. communities after natural or other disasters. Recipients of this temporary parole, however, do not have an official immigration status. They are merely permitted to stay in the United States for an amount of time determined by DHS, after which they must leave the country.

With the International Entrepreneur Rule, DHS first articulated its use of parole for individuals who could provide a “significant public benefit” by starting innovating businesses with high potential for growth in the United States. In the rule, DHS outlined the requirements for the types of entrepreneurs and startups that would be considered eligible for entry into the United States with parole. To be considered for parole, entrepreneurs must:

Up to three entrepreneurs per startup can qualify for IER parole. If an entrepreneur (or entrepreneurs) and their startup meet these requirements, DHS may grant them parole for up to 30 months. After this period, the entrepreneur can apply for a single extension of parole for at most another 30 months, if the startup continues to provide a “significant public benefit” as proven by increases in capital investment, job creation, or revenue.

It is important to note that U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) processes IER applications and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officially grants IER parole at a port of entry. When an IER petition is approved, USCIS recommends that CBP grant the beneficiary entry into the United States for a certain amount of time up to 30 months. Then CBP can decide whether to follow that recommendation, or grant entry for a shorter period.

While the IER is not a typical immigration pathway, it fills a gap for entrepreneurs that more common immigration statuses cannot satisfy. Other statuses have lengthy processing times or backlogs which are incompatible with launching a startup (H-1B and EB-2), require a significant amount of personal wealth (EB-5), necessitate establishing the business in another country first (L-1, E-1, and E-2), or require the entrepreneur to already be at the top of their field (O-1 and EB-1), which is uncommon for most startup founders.

The IER is currently the only path to work in the United States that was designed specifically for attracting talented startup entrepreneurs, and should be reimplemented swiftly so it can achieve its full potential. In addition, the IER gives U.S. investors a strong interest in ensuring that the entrepreneurs are successful and that they integrate well while in the United States. Qualified investor organizations are highly motivated to put their money into strong teams with a high capability to execute.

Unfortunately, implementation of the IER has had a host of issues. On January 17, 2017, the final rule for the IER was published in the Federal Register, just days before President Trump was inaugurated. It was supposed to come into effect on July 17 of that year. On July 11, however, DHS delayed the effective date with the stated intention of rescinding the IER completely, thus dissuading potential applicants from taking advantage of it. The Trump Administration was against any expansion of parole authority and directed its energy to reducing immigration levels to an unprecedented extent.

In December 2017, however, the U.S. District Court for Washington, DC ordered DHS to stop delaying and to begin accepting IER applications. It did so, grudgingly, warning applicants that the administration still sought to eliminate the program.

Then, in May 2018, DHS issued a proposed rule in the Federal Register to formally rescind the IER, creating even more confusion and casting another cloud over the program. Even though this rescission rule was never finalized and therefore never took effect, the contentious early history of the IER stunted its potential and convinced an untold number of entrepreneurs to look elsewhere to start their businesses.

For those few who nevertheless chose to pursue entrepreneurship in the United States via the IER, the application process was grueling. Attorney Elizabeth Goss, one of the few immigration lawyers in the country who had a client approved for IER parole thus far, notes that many of the difficulties she faced during the application process were likely related to the unfamiliarity DHS had with implementing the rule. The two biggest pain points were the difficulty of obtaining investment history information from her client’s investors and the discretionary nature of IER parole length.

First, in order to be approved, the applicant must provide proof that their investors are “qualified” as defined in the IER. This includes having the investor organization prove that it has invested in startup entities worth no less than $600,000 over a five-year period and that at least two of these startups created at least five full-time jobs and generated at least $500,000 in revenue with an average annualized revenue growth of at least 20 percent—all information that is not commonly shared with outside parties.

Next, after compiling all of the necessary evidence and fielding requests for additional information from the agency, Goss’ client was only granted a year-long parole by CBP instead of the full 30 months. The entire application process itself took one year.

Former USCIS Deputy Chief of the Adjudications Law Division Sharvari Dalal-Dheini, who observed the initial implementation of the IER within the agency, echoed some of Goss’ points about the difficulty of obtaining IER parole. She agreed that the standards in the IER regulations are very high and have likely dissuaded potential entrepreneurs from applying. In particular, the requirements to be considered a qualifying investor are restrictive, as the investor organization must be majority-owned by U.S. citizens or permanent residents. It is not uncommon, however, for high-profile investor organizations to have foreign investors.

That said, many groups have strongly advocated for the IER, noting that there is no other adequate pathway for startup entrepreneurs. Greg Siskind, another leading immigration lawyer, explained in a public comment that IER parole is no less risky than holding a nonimmigrant work visa, at least as long as USCIS has rescinded its policy of deference for prior determinations for status renewals. He also outlined how other immigration pathways are inadequate for startup entrepreneurs, a summary of which can be found in the table below.

Table 1: A comparison of alternative pathways for startup entrepreneurs and their drawbacks

| Potential pathway for entrepreneurs | Requirements | Reasons pathways are not adequate for startup entrepreneurs |

|---|---|---|

| L-1 – Intracompany transferee (temporary status) |

|

|

| H-1B – Specialty occupation worker (temporary status) |

|

|

| O-1 – Extraordinary ability or achievement (temporary status) |

|

|

| E-1 and E-2 – Treaty traders and investors (temporary status), |

|

|

| EB-1 – First preference, employment-based (permanent residency) |

|

|

| EB-2 – Second preference, employment-based (permanent residency) |

|

|

| EB-3 – Third preference, employment-based (permanent residency) |

|

|

| EB-5 – Immigrant investor program (permanent residency) |

|

|

The IER, if allowed to work properly, fills an important gap in the immigration system. The Biden Administration has an opportunity not only to revive the IER but to address some of the implementation difficulties of the last several years and make the program more effective. There are three levels of changes that can be made to strengthen the IER:

At the broadest level, for the IER to live up to its full potential, it needs the credible backing of the administration, publicly committing to the rule and its improvement based on feedback from the broader community. Immigration lawyers play a vital role in guiding their clients through the labyrinthine process of navigating various immigration channels and they are unlikely to recommend their clients pursue the IER unless they believe that it is a “real” program with well-articulated standards and a reasonable processing timeline.

This can be achieved in a number of ways. First, vocal support and recognition of the program by the White House and high-ranking administration officials will raise the profile of the IER and indicate that the program will be actively administered and improved over time.

Second, DHS can make a concerted effort to market the program, highlight the IER specifically as an option for qualified candidates, compare the different pathways for legal residence for talented international students, and be sure to circulate such information with U.S. colleges and universities where many potential entrepreneurs will be studying.

With the IER being a relatively new program, it is likely to face additional implementation barriers that are difficult to anticipate beforehand. Accordingly, it will be important to create and maintain real-time feedback mechanisms that allow external stakeholders to flag unnecessary bureaucratic hurdles or improperly targeted eligibility criteria. One option for facilitating feedback would be to use an existing DHS council under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) to get real-time implementation suggestions from such stakeholders as immigration lawyers, venture capital firms, and international student groups—for example, the Homeland Security Academic Advisory Council (HSAAC). Questions regarding the optimal investment size minimum, the structure of qualified investment groups, and the process for U.S. border entry will be better addressed with the buy-in and input of the communities that are most impacted by them.

Given the fairly wide scope for agency discretion in the administration of the IER, there are many ways of improving implementation simply by issuing new guidance documents and streamlining operations, among other subregulatory actions that do not require altering existing regulations.

As described above, past applicants to the IER program were approved by USCIS but granted entry by CBP for a shorter period of time than the full 30 months. This increases uncertainty for future applicants and makes it much more difficult for an entrepreneur to launch a startup and cultivate its success prior to the parole period ending. In addition, to obtain a renewal IER status, the startup must meet stringent requirements, and shortening the amount of time the entrepreneur has to satisfy those requirements adds a significant burden—dissuading future applicants and forcing entrepreneurs with innovative ideas out of the country prematurely. This could be mitigated by issuing internal guidance that directs USCIS and CBP to grant beneficiaries the full 30 months of parole, absent extraordinary circumstances.

In addition, one of the biggest pain points during the application process is proving that an entrepreneur’s investors are qualified. Often the information that is required is not publicly available or is proprietary. For Goss’ client, it took an entire year to gather the right information to satisfy the investor requirements. USCIS could simplify the process, making it clearer what documentation is necessary, and making it easier for investing organizations to provide information without compromising sensitive financial data in certain cases. In addition, once an investing organization has proven to USCIS that it is qualified, it should be allowed to refer back to its previous documentation for future IER approvals for a period of time (e.g. three years). This would encourage more U.S. investors to become willing participants in the IER program, since the bureaucratic hurdles would be viewed as more a one-time cost rather than a recurring issue.

An alternative approach to streamline the process of verifying qualified investor status would be to look to the “accredited investor” process adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for private placements. Rather than have investors submit sensitive financial data to the SEC, the agency allows investors to submit a sworn affidavit that indicates the investor meets the standards for accreditation under penalty of perjury. This process is much simpler for investors and the SEC alike, and would surely save DHS both time and resources.

Lastly, DHS could issue further clarification on what would satisfy the “alternative evidence” standard for IER eligibility. If an entrepreneur does not have $250,000 in investor funds or $100,000 in government grants or awards, they can still qualify for IER parole if they can prove that their startup has “significant potential for rapid growth and job creation.” USCIS guidance in a Policy Memorandum could encourage adjudicators to place particular weight on evidence that the startup will:

While guidance documents can be a useful near-term tool to improve the functioning of the IER and allow flexibility for the agency, ultimately the program will have more stability if long-term changes are established in regulation.

First, new rulemaking should be used to formalize guidance once the agency has worked out more definitive and objective standards around a more durable definition of “qualified investor” and evidentiary standards for “rapid growth and job creation.” Increasing stakeholder certainty in the long-term viability of the rule will be key to its uptake and success.

Second, new rulemaking should be used to help bridge the gap between the IER and existing immigration pathways for permanent residence. It would be a perverse outcome if successful entrepreneurs were forced out of the country after their parole term concluded. Policymakers should identify natural “bridge” statuses for individuals on the IER to graduate into, and make the operation of a growing U.S. business an explicit criterion for eligibility. For instance, the EB-2 green card overlaps well with the skill sets and purpose of the IER, as it is meant for a “foreign national who has exceptional ability.” Almost by definition, the successful launch of a growing U.S. business should demonstrate exceptional ability. Modifying the EB-2 and National Interest Waiver rules, as described in Table 1, to explicitly include entrepreneurship as a qualifying criterion will provide a natural on-ramp to permanent residence and the continued long-term operation of the entrepreneur’s business.

Finally, it is important to note that while the IER is a promising tool for making the United States a welcoming home to international entrepreneurs in the immediate term, even with all the proposed changes above, it may not be sufficient. The uncertainty around long-term permanent resident status in the United States, which cannot be granted through parole alone, and uncertainty around future political changes to (or suspension of) the program could prevent the IER from being maximally effective. Over the longer term, Congress should pass more enduring startup visa legislation, expand the number of green cards available, and reform existing immigration pathways such that they would be more suitable for an international entrepreneur seeking to start a firm in the United States.

In fact, not one but two statutory pathways for entrepreneurs were already passed by the Senate in its bipartisan 2013 comprehensive immigration bill. Congress should consider reintroducing these pathways, updating them with the best parts of the IER while maintaining DHS’ flexibility. Such changes include:

In addition to these changes, Congress should make a point to gather stakeholder feedback on the details, particularly on the definition of a qualified investor, to ensure that no legitimate investors are barred from participating.

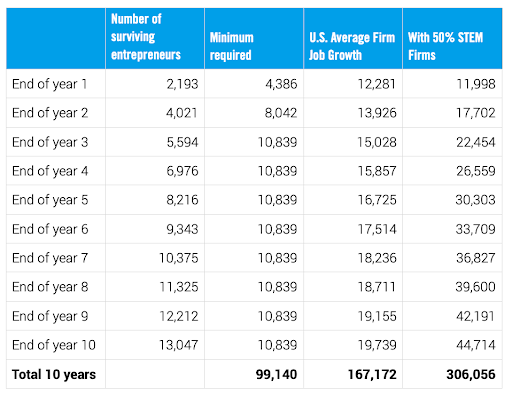

We have developed a few baseline estimates as to the number of jobs that could be created through the IER by using a similar methodology as the one used by the Kauffman Foundation in their earlier paper estimating the job impacts of a statutory Startup Visa.

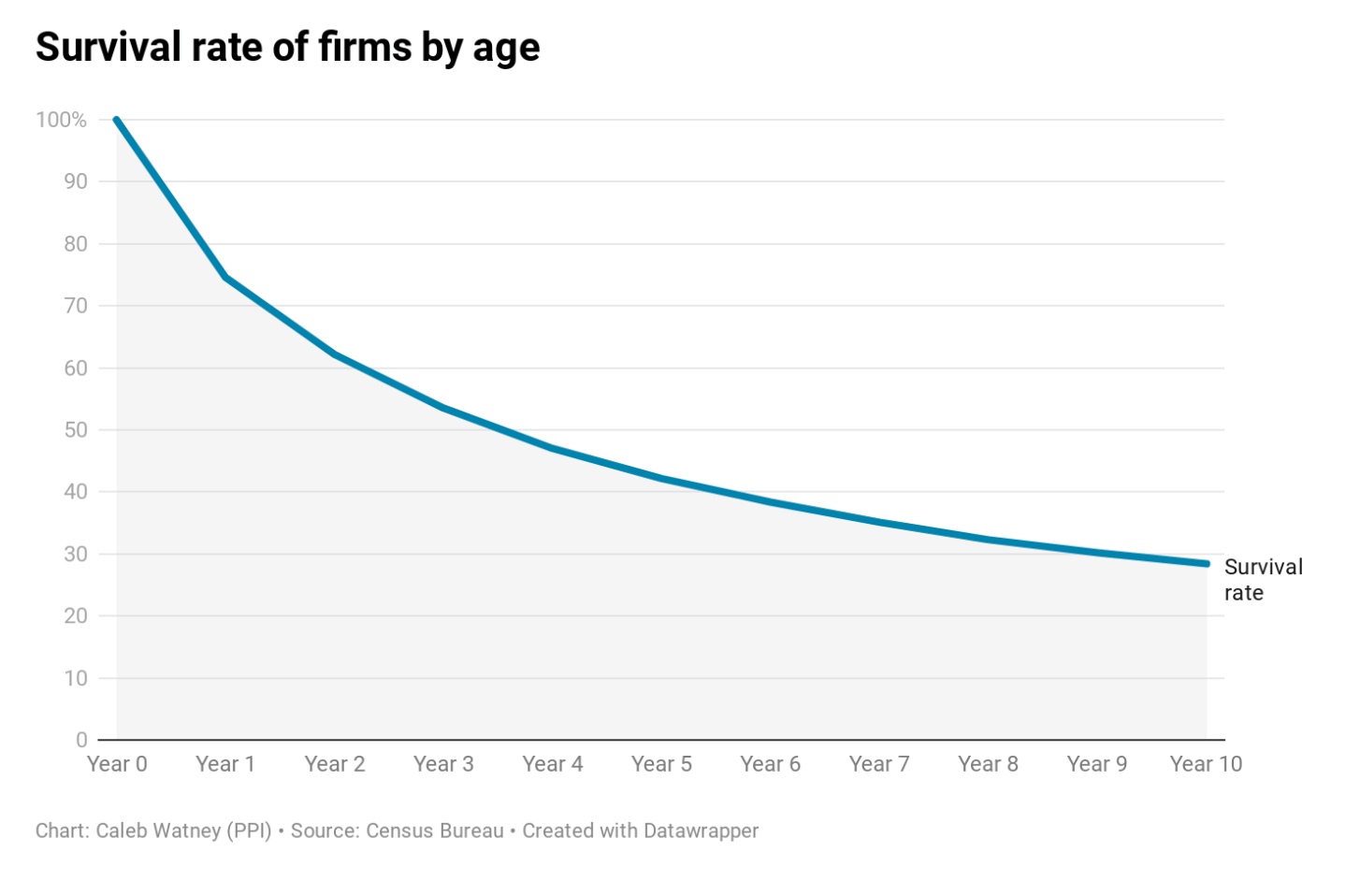

To begin with, we use the DHS estimate that the IER will attract 2,940 entrepreneurs per year with one founder for each firm. However, starting a business is difficult, and some percentage of firms will fail each year. Using the Business Employment Dynamics (BED) dataset from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, we can see the percentage of firms starting in 2010 that survived from year to year among the “Professional, scientific, and technical services,” category which we believe to be the closest analogue for the types of firms likely created under the IER.

Then, we can create an estimate for the total number of surviving entrepreneurs that remain in the country that entered through the IER and add the addition of a new entrepreneur class that joins each year.

Finally, we can apply a simple job creation rate under a number of scenarios. Under the most conservative scenario, we estimate the number of jobs created if surviving firms create only the required 5 jobs over a 30 month period to satisfy the terms of the program and be eligible for parole renewal. We then assume no further job growth while the firm survives.

In the second scenario, we estimate job growth under the assumption that each of these firms mirrors the average job creation rate of a U.S. firm its age so long as it survives. To estimate this we used the BED dataset and the average employment of firms at age 1, age 2, age 3, and so on starting in 2010.

Finally, we consider the scenario in which 50 percent of these firms are in STEM fields and have a corresponding higher rate of job growth. We use the estimate of Vivek Wadhwa from a prior Kauffman study, which found that the average immigrant technology or engineering startup in their sample from 2006 – 2012 had 21.37 employees. The other 50 percent of firms are assumed to mirror the average U.S. job creation rate for a firm that age. Fundamentally, this third scenario is trying to capture the idea that while the average US firm begins to slow down the rate of job creation after the first several years, the types of entrepreneurs and investors likely to make use of the IER are those disproportionately in the” high-growth young firm” category that will sustain fast rates of job growth overtime.

The table below shows these three scenarios applied to the projected entrepreneur population:

After 10 years, the IER could bring in more than 13,000 new businesses and create more than 300,000 jobs in the United States. While this projection is already promising, the IER has the potential to contribute even more to the economy.

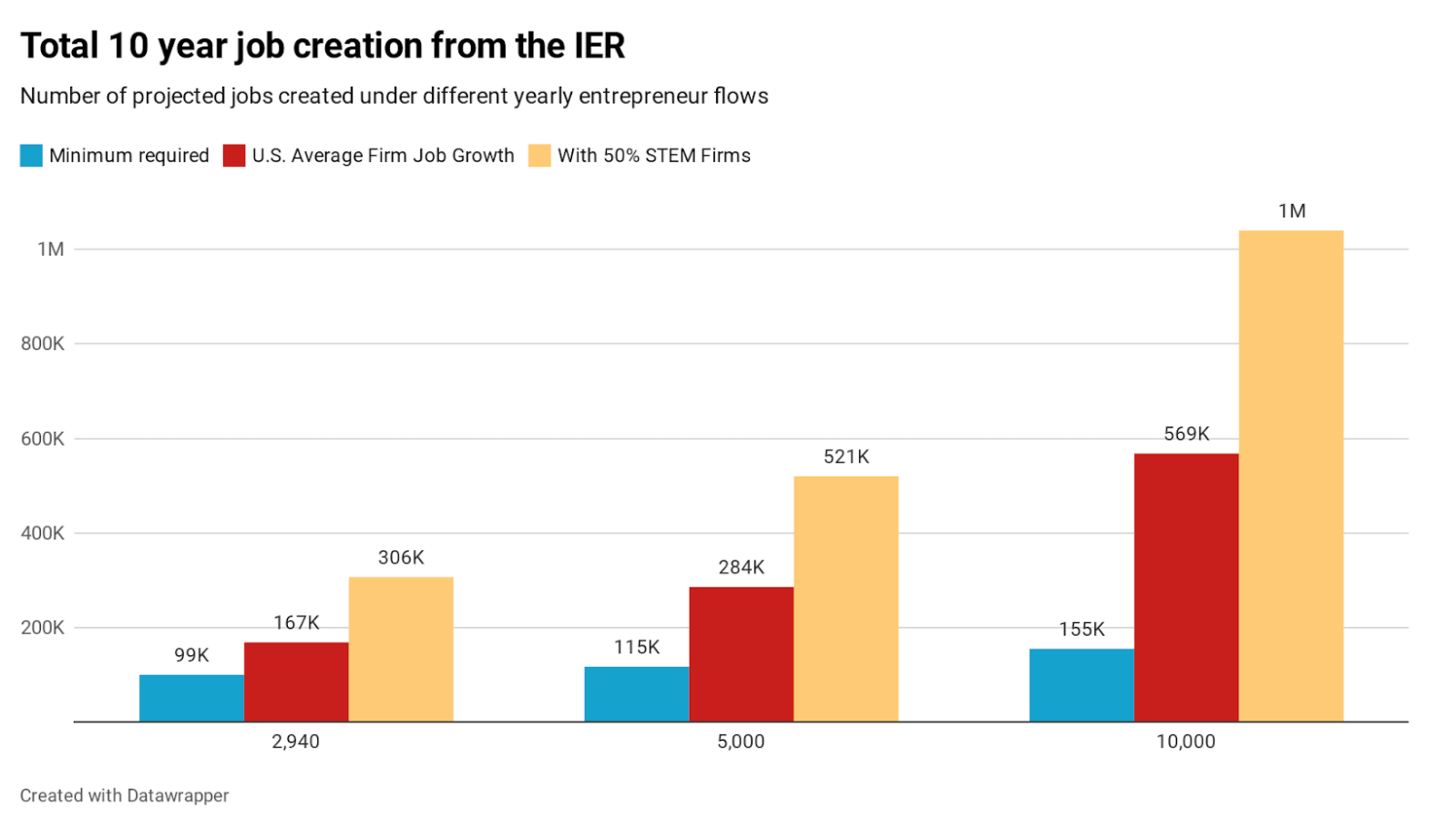

The above job creation projections are all based on the assumption by DHS that a fully implemented IER will attract 2,940 entrepreneurs per year—but there is good reason to expect a much higher level of uptake. Entrepreneurs, investors, and local communities are all responsive to potential opportunities, and if they perceive that the IER program is workable and stable for the immediate future, they are likely to adapt their own practices to better utilize this pathway.

➤ Venture capitalists

For instance, firms and individuals that have a proven track record of investing in international entrepreneurs through the IER may begin to specialize in such cases and seek out promising potential entrepreneurs from around the world and encourage them to apply for IER status in the first place. Today a few groups like Unshackled Ventures specialize in finding, investing in, and bringing international entrepreneurs to the United States through the limited immigration pathways that already exist. With a dedicated path to entry for international entrepreneurs, many more such firms would likely come to exist. Similarly, major venture capital groups with significant foreign investment may reorganize their structure to ensure that their U.S. investment arms are majority-owned and controlled by U.S. citizens and permanent residents, thereby satisfying the eligibility requirements for qualified investors under the IER.

➤ State and local governments

States and local governments frequently award competitive research grants on a wide range of R&D and business development topics, and would likely expand these efforts if they also entailed a legal path to residence for international entrepreneurs. Legislative proposals like the Economic Innovation Group’s “Heartland Visa”—largely endorsed by the Biden presidential campaign—would have Congress create a new immigration pathway to promote regional economic development through state- and city-sponsored visas. Essentially, a pilot version of this proposal could be pursued immediately through the IER as states and localities that award at least $100,000 to promising international entrepreneurs could thereby ensure the creation of a new startup in their region.

➤ International students

In addition, international students studying here would know ahead of time that a path exists for those starting a successful business, and could organize their studies and plans accordingly. This could end up having a very large impact, given the startling finding that foreign-born STEM PhDs are not currently founding or working for U.S. startups at the rate we would expect given their stated career interests.

Economists Michael Roacha and John Skrentny found that immigration barriers are a significant deterrent in these PhD graduates’ ability to realize their startup career interests, compelling them to either leave the country or work at larger U.S. firms where visa pathways are more well-established.

“Foreign PhDs are as likely as U.S. PhDs to apply to and receive offers for startup jobs, but conditional on receiving an offer, they are 56 percent less likely to work in a startup. This disparity is partially explained by differences in visa sponsorship between startups and established firms and not by foreign PhDs’ preferences for established firm jobs, risk tolerance, or preference for higher pay. Foreign PhDs who first work in an established firm and subsequently receive a green card are more likely to move to a startup than another established firm, suggesting that permanent residency facilitates startup employment. These findings suggest that U.S. visa policies may deter foreign PhDs from working in startups, thereby restricting startups’ access to a large segment of the STEM PhD workforce and impairing startups’ ability to contribute to innovation and economic growth.”

This is further evidence that America has a latent population of foreign-born entrepreneurial talent that could be effectively unlocked by creating better pathways for them to stay in the United States while launching or working for a startup.

In short, the prior estimate of IER leading to 100,000 – 300,000 jobs over 10 years, generated by fewer than 3,000 startups per year, is likely a lower bound. Consider that angel investors in the United States fund about 63,000 startups per year, most of them in STEM fields. Roughly one quarter of tech startups have at least one foreign-born founder, who was able to stay in the United States, thanks to an immigration pathway not designed for entrepreneurs.

With a permanent, predictable pathway for international entrepreneurs, it is reasonable to expect far more than 3,000 additional founders to choose the United States over other alternatives, leading to significant job creation in the aggregate. If we instead adjust the number of incoming immigrant entrepreneurs to 5,000, more than 500,000 jobs could be created over 10 years. And if 10,000 immigrant entrepreneurs came each year, more than a million jobs could be created over 10 years.

It is also worth remembering that today’s startup can become tomorrow’s industry-shaping giant. Among America’s first four trillion-dollar companies, one was co-founded by an immigrant (Google), two were founded by the children of immigrants (Amazon and Apple), and one is run by an immigrant (Microsoft). These four companies alone employ over 676,000 people in the United States.

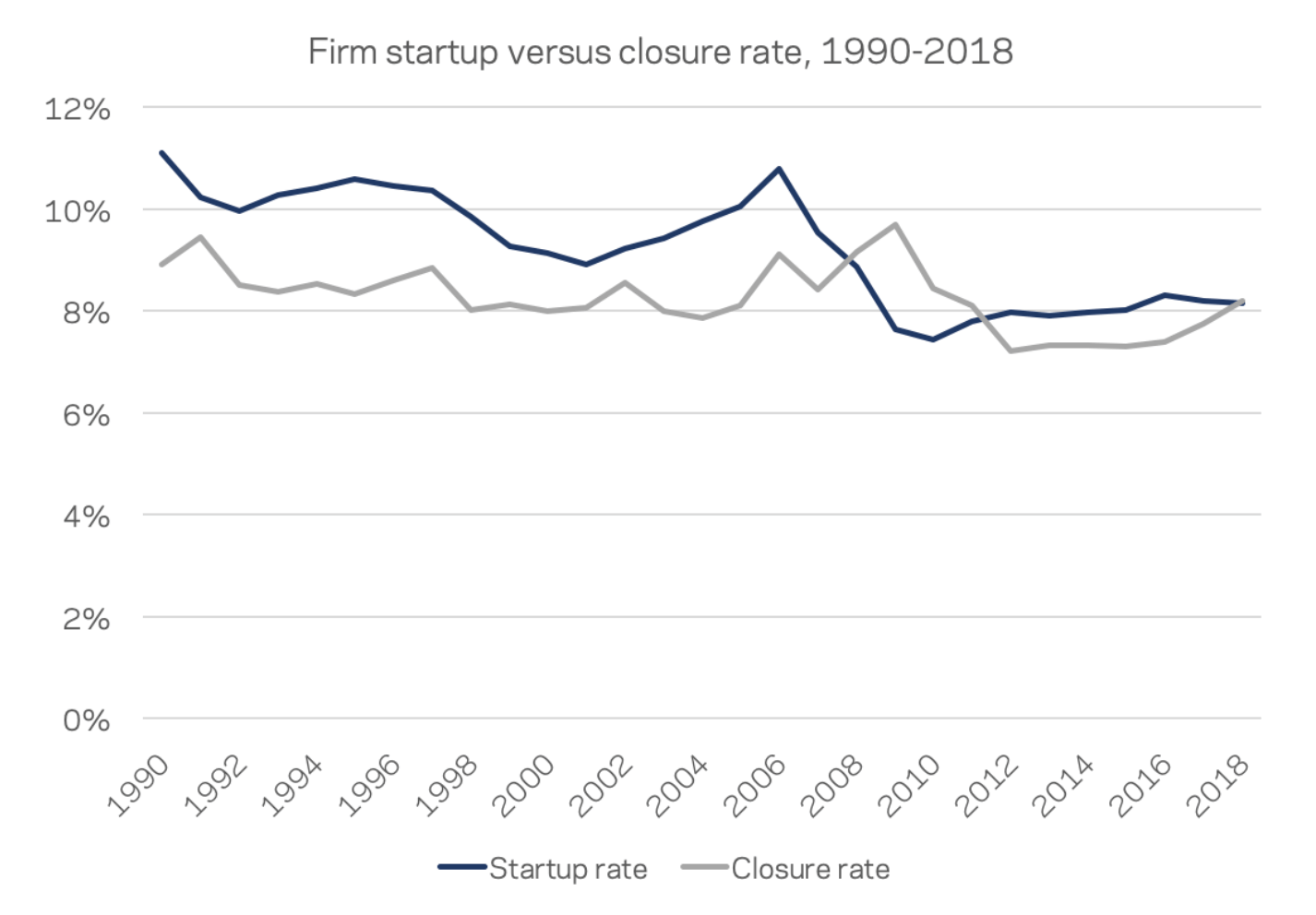

In addition to the direct job gains, adding more international entrepreneurs could help reverse the decades long decline in American economic dynamism. Fewer American firms are being started, fewer firms are exiting, and the resulting slowdown has coincided with a slowdown in productivity growth.

Stimulating the U.S. economy with more international entrepreneurs would very directly increase the number of firms started in the country, but increased competition could also force U.S. incumbents to become more nimble and adopt new technologies and products to survive and thrive.

As concern continues to build on both the right and the left that the United States may be losing its status as the world’s leader in science and technology, one of the easiest ways to solidify this lead would be to allow international entrepreneurs to build their companies in the United States rather than in competitor nations. For emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, drones, quantum computing, and biotechnology, this is especially important.

Countries all over the world are competing to attract the best talent to their shores. These efforts include developing an environment that supports the establishment and growth of promising startups. The United States, however, has no statutory immigration pathway designed for entrepreneurs. To address this unnecessary handicap, DHS established the International Entrepreneur Rule in 2017 to welcome foreign-born entrepreneurs with innovative ideas with high growth potential. Unfortunately, the IER was never fully implemented by an administration determined to eliminate it.

IER has survived, however, and now is the time to strengthen it. This paper provides a suite of recommended improvements to bolster the IER and ensure that the United States is better positioned to attract international entrepreneurs. Tens of thousands of entrepreneurs and subsequent economic growth are at stake. The IER is a valuable tool in the economic toolbox—not only for the federal government but for states and localities as well—which can attract entrepreneurs to settle throughout the United States. It should be fully implemented and reinforced. The United States has a renewed opportunity to solidify its reputation as the best place on Earth to start and grow a new company.